tl;dr I did the Three Passes Trek through the Khumbu region and climbed Island Peak. It was cool, and if you hike/climb at home you can definitely do it too. Get the GPX of my trip here. Check out the pictures I took in the gallery (or in this article - there are a lot). If you want some beta/tips, scroll to the bottom of the article.

Karma

For my first trek in Nepal, I had no idea what I was going to do. But I was signed up for a climbing course in November, and I had offered to bring over a bag of donation clothing for the Nepali students. Karma Sherpa, the Nepali head of the course, and his wife met me to pick up the bag promptly on arrival at my hostel. I told him my plan to bum around the mountains for 2 months until the course started, and he promptly sent me an itinerary for the Three Passes Trek, which traverses the high mountain passes separating the 4 major valleys of the Khumbu region. As a bonus, after my last pass I'd climb Island Peak, a small 6100m peak, with Karma as he acclimatized for his second ascent attempt of Barun Tse, a burley 7000m mountain just nearby. Over a delicious lunch at his home the next day, it was decided. I'd do the Three Passes, and I'd go with Pema Sherpa.

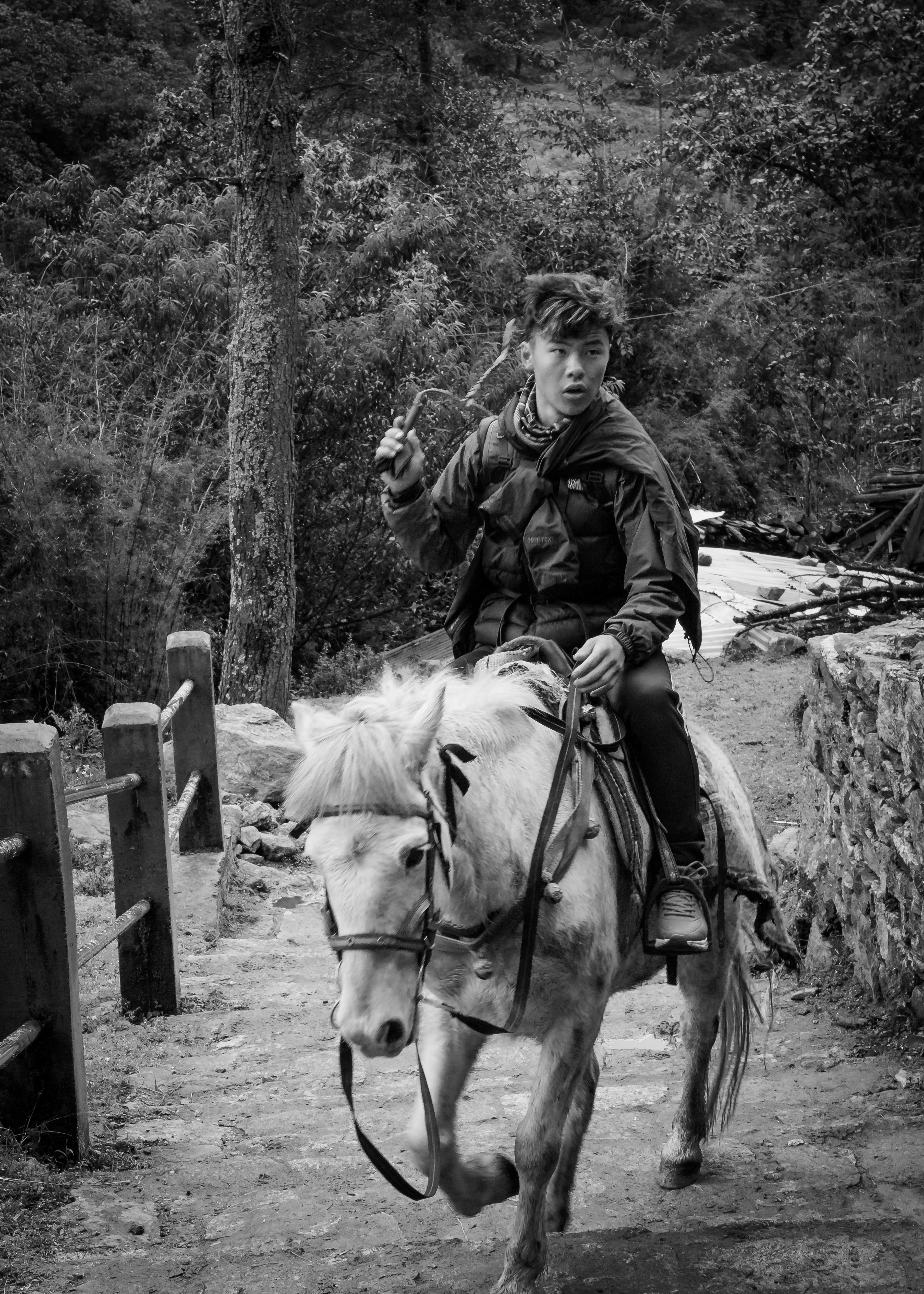

Pema

Pema Sherpa studied as a monk for many years, and summitted Everest in monk's robes after a month of prayer at Camp 2. His name means "lotus flower" in Tibetan, and he is from the same village as Karma. He's also kind of a dog. Pema has been my guide and constant companion for the past month, and for that I am honored. He's come through clutch so many times, and has taught me invaluable lessons about Nepali, tantric buddhism, and life in the hills.

Getting There

To trek in Khumbu, you first have to get to Khumbu. And it's not gonna be easy. The main entry point into the region is the airport at Lukla, which is directly south of the main valleys. During the peak trekking season (late Sept - early Dec), flights don't go directly from Kathmandu to Lukla. For this, there are many reasons, but the one that makes the most sense to me is weather. The Lukla airport is notorious for crashes, mostly caused by loss of awareness. The weather, especially early in the season, can change remarkably fast. A bluebird day can within minutes break down into a mess of thick, low-lying clouds and torrential monsoon rains. Flying rickety old prop planes with no automatic instrumentation and phenomenally low margins of error on one of the world's shortest runways, at least one pilot a year simply dashes his vessel on the side of the mountain. The flight to Lukla from Manthali, where planes depart during tourist season, is about 20 minutes. From Kathmandu, 45 minutes. That 25 minute savings, ideally, allows air traffic control to make better predictions and is the difference between seeing the mountains and becoming part of them.

At 3 am I, along with Pema and John (a client of Karma's doing a different trek), crammed into a regular city taxi and didn't buckle up for a 4 hour ride through the foggy, pitch-black night on the windiest, bounciest, steepest, most insanely potholed dirt "roads" I have ever experienced to arrive in Manthali for the 7 am flight we had booked. Upon arriving at the airport, it was clear that our ticket didn't matter at all. Because of the late monsoon, nothing had left the ground for three days. There were thousands of people milling around the tiny airport, nervously eyeing the sky. Thinking the worst, John and I settled down with our coffee. He was discussing the possibility of returning to Kathmandu for the night when Pema ran over and told us to grab our bags. He had waded into the seething mass of people vying for seats on the day's flights, and the next scheduled run had three free slots. Ours was the only group with exactly three people. We hustled through a sparse security check and arrived at the gate, incredulous. The craft shuddered and rocked side-to-side as the prop started, and into the ominous gathering of clouds we went. The clouds obscured our view of the mountains, but thankfully not our pilot's view of the runway. He touched down deftly to a smattering of nervous applause. We had made it to Lukla.

What can you do?

In Namche Bazaar, two day's walk from Lukla and the largest settlement in the Khumbu, we stayed at the Shangri-La Guest House. The hostile weather ensured some quiet; only one other tourist stayed that night. The owner is originally from Namche, and has run the lodge since he built it in 2004. With the earnings from his business, he was able to send his daughter to school in Kathmandu. She's now studying nursing in Texas. He's visited her, and was surprised by just how flat it is. Through her schooling, his daughter is fluent in Nepali and English, but knows little Sherpa. When I asked him how he felt about his success possibly driving his children away from their culture, he shrugged and laughed. "Ke garne (what can you do)?"

Om, Mani, Pedme, Hum

There is magic in the mountains, this I've known for years, but nowhere has it been more evident to me than in the Nongpa Valley. The Nongpa La, the high mountain pass at the valley's northern end, has historically been the trade route between Nepal and Tibet. As such, the valley is rich with Buddhist tradition, glittering stupas and solemn monasteries. On our way up from Namche, we passed a nun returning to her home high on the hill above the village of Thamo. Pema, being the guy he is, chatted her up in Tibetan and took her bag. She migrated over the pass 19 years ago, spoke no English and very little Nepali. Upon arriving in Thamo, she invited us to the nunnery for tea and biscuits. Sitting there amid only the sounds of wind, prayer bells, and bustling in the kitchen, I felt such profound peace I couldn't help but cry.

Forcing It

The one guesthouse in Khumbu that I can unambiguously recommend is the Yak Hotel in Thame. Pema and I were treated to free welcome tea on arrival, they heaped food on us past what we ordered, their gas shower actually worked (it would be the last I'd take for two weeks), and it's the only place I stayed past Namche with outlets in the rooms. If you find yourself in the Nongpa Valley, stay there.

Our first pass, the Renjo La, would require us to ascend to 5300 meters. To acclimatize, we decided to climb Sumdur Peak, a hill west of Thame that tops out at 4770 meters. On the way, I understood why the trip was necessary. At 4400 meters my head throbbed, my heart pounded, I was short of breath and stumbling. Gradually I regained control of my breath, and the well-defined path ensured the 4770 summit came easy enough. There I checked Gaia on my phone and, of course, saw that the true summit was further down the ridge and higher, itself reaching 5300 meters. Beyond our position the path disappeared, leaving only exposed class 4 scrambling on a ridge that sharpened to a knife edge at points. Still, Pema didn't take much convincing. We'd continue, but we wouldn't force it. If we lost visibility, or if the rocks started collecting snow, we'd turn back. To this point, the clouds' habits of retreating at dawn only to return in force by the late morning was holding. By 10 am we were socked in. Snow appeared as we gained elevation, and the melt combined with the moisture in the clouds to make our footholds slippery and insecure. At 5100 meters, stopping to take stock of the thickening snow under our feet and the inscrutible terrain ahead, we made the call the turn back. After hot tea and biscuits, we started our descent to Pema's resounding call of "SUCCESS!!"

The Renjo La

The clouds decided to break their habit on the day of our first pass. At 4 am, listening to the sound of rain pattering on the tin roof in my frigid room, I wondered if we'd call it to wait for better weather. Nope. Pema and I left our lodge promptly at 6:30, letting out calls of "SOU SOOO" in unison (Sou so is, as far as I understand it, Sherpa for "YEW"). As the rain turned to hail turned to snow, we were caught up by a group headed to climb Cho La Tse. Following their colorful umbrellas for a while, I caught sight of our destination at the top of the pass and forged ahead. Here the mantra Pema had taught me in the monasteries of the valley served me well. After a deep pressure breath to combat the altitude, I counted out my breaths in groups of 4. In, Om. Out, Mani. In, Pedme. Out, Hum. In this way, the pass came eventually.

After an hour of descent, the town of Gokyo appeared like a beacon on the lake for us weary travellers. The smell of yak dung-fueled hearth fires hit my nose hard as we arrived and, although grateful for the warmth it indicated, the odor combined with the altitude and my exhaustion brought up a nausea that stopped me in my tracks. We pulled up to a packed lodge and bakery, its shelved lined with chocolate cakes. Chocolate.

As luck would have it, the weather broke that very afternoon. Someone told me there was a great sunset by Cho Oyu. I followed his pointing hand, thinking I would set up by the Cho Oyu Lodge & Restaurant or something. It floored me to see Cho Oyu itself, glimmering proudly in the cloudless sky. I was finally here, in the home of the mountains.

Race!

After the first pass, I felt like I had my sea legs at altitude. For me, it's a matter of conscious breathing. You have to force it, to breathe harder than you think you need to, to inhale sharply and to exhale quickly and completely. I actually think I'm okay at it. So I've started to get competitive.

Outside of Gokyo is the hill of Gokyo Ri, a 5300m peak that offers sublime panoramic views of the entire adjacent range. Starting up with Pema, I decided that I wanted to push. I found my rhythm and set in motion, while Pema took a different path. Once I had lost sight of him, I figured we were racing. So I raced. After a while he called me on the radio and said something I couldn't understand, but I assumed meant that he was close to the summit. I pushed even harder. After an hour I made it to the top, but Pema wasn't there. I called him. He was huffing and puffing, a hundred meters down, and said I should take pictures and meet him on the way back. Hell no dude, get up here! So he did shortly after, but if it was a race, I did win.

A few days later in Gorak Shep, the last town before Everest Base Camp, we chatted with Kangchenkanguru Sherpa, a hardened old climbing guide that has seen multiple 8000 meter summits. He too was guiding a group through the Three Passes, and tomorrow we'd both go up Kala Pattar, a 5600m hill and the most famous Everest viewpoint, at sunrise. I got a late start, 30 minutes after Achu Kang (Achu means older brother in Sherpa), but I was determined to catch him up. I steamed ahead of Pema and began systematically overtaking groups on the muddy switchbacks. Snot streamed from my nose because of the cold but I let it run - I couldn't risk breaking my rhythm to stop for something minor like that. I probably looked an absolute sight as I arrived at the summit to see Achu Kang towering over me, smiling, hands in his pockets. "How's it going!" he bellowed. He'd been up there for 10 minutes already.

Little Lobuche

The air was cold in Lobuche village, owing to its impressive altitude of 4900m, and I was restless after an easy day's walk. Pema told me I might get reception if I hiked up the hill behind town, so I set off. At the top of the hill, nothing. But off in the direction of Lobuche were three small, craggy peaks that looked like fun scrambles and, who knows, maybe I'd get reception up there!

The first peak came easy enough, with a well-defined trail ending in some low 3rd class talus scrambling. This peak is commonly done as acclimitization for Everest Base Camp.

After the first peak, I dropped down to climber's left and found a nice little dihedral to the next one. 3rd/low 4th class scrambling up that line made the second peak come easy.

Looking onward, the third peak looked dauntingly far away. I took stock: it was late, about 2 hours before sunset, and I didn't even have a water bottle. Oh but it looked so fun. In fits and starts, I started to descend on climber's left of the second peak and set myself on going for the third. After a short downclimb, I hugged the second peak tight and regained the ridge. The best path is marked with a cairn, and I added another. On the ridge, a shallow walk over heather took me to the face of the third peak. The first time, I decided to traverse left and climb up on the edge of an impressive drop-off. A better way, which I took a few days later, is to climb straight up the face. It looks steep and intimidating, but the rock is solid and presents obvious, juggy knobs for holds. Either way, the scrambling is thrilling and the exposure immense.

Reaching the third peak, in the company of Lobuche East's impressive east face and with the din of the village far below me, I felt absolutely sublime. I still didn't get any cell service, but it remains the most fun I've had yet climbing in the Himalaya. Yet the day was growing late and thick clouds were rolling in to herald the evening. I asked Pema later how he felt, and he grabbed his heart. I must have worried him sick. I called down to him on the radio, asked him to order me some Dal Bhat, and headed down.

There is so much opportunity for scrambling adventures in these hills, and I think someone oughta do something about it.

Imja Tse

After our last pass, the Kongma La, we arrived in the village of Chukkung amid a bit of drama. Karma's client had cancelled on him, and the Barun Tse climb was off. Karma had taken a helicopter back to Lukla. In his stead, he sent Sonam Sherpa, another Sibuje man and Pema's good friend, to take me up Island Peak (aka Imja Tse). He arrived by helicopter and, after a night's rest, took me through a gear check and short skills practice. We then set out for base camp, a short 2 hour walk. Dinner was garlic soup, popcorn, tuna pizza, and spaghetti in the mess tent, then off to bed. At 1 am we rose, the condensation frozen on the walls of our tent in the 15 degree chill. I immediately broke one of the laces on my hand-me-down Spantik boots as I put them on, and hastily repaired it with a fisherman's bend because I had left the spare lace in town.

What they don't tell you about Island Peak is that most of it is either dirt or rock. If I were to do it again, I'd definitely start in trail runners and carry my boots until the snowline. We started later than most groups, and passed almost everyone on the dirt. A short step of scrambling over a thin ridge got us on the snow, where we perfunctorily roped up even though the path was well traveled and without crevasse danger. The crux of the route is about 4 pitches worth of 60-degree compacted snow and ice culminating in a knife-edge summit, all of which are protected by thin static lines fixed at the beginning of the season.

Without the lines, making the summit of Island Peak would be an an interesting challenge of climbing steep snow while assessing and managing risk at altitude. With the lines, it was drudgery. The only upside is that it made rappelling a breeze, although the integrity of the lines should be suspect after the amount of traffic they receive.

At the same time, I understand why they're there. In America and Europe, an entire country's economy doesn't depend on the revenue generated by tourists climbing its mountains. If you want to go up a mountain in the Cascades and die trying, that's on you. In Nepal, the economy is underpinned by mountain tourism and every mishap is a disaster. We passed an astounding number of people on the way up that had no business being on a mountain like that. Without the lines, they hopefully wouldn't even try. With the lines - and their guides - it's an achievable challenge they can set for themselves that also benefits Nepal's economy. It's not how I enjoy climbing, but I appreciate why it exists.

Ama Dablam

When I ask Karma, a multiple 8000er climber, which is his favorite mountain to climb, he doesn't hesitate. Ama Dablam.

When I talk to Pema about what mountains he wants to climb, he breathes in deeply. Ama Dablam. My faaaavorite.

When I ask Achu Kang about Ama Dablam, he recoils. It's hard! Steep climbing up slippery, icy rock! A precipitous high camp on a sliver of a ridge!

It presides loftily over its neighbors, is visible from almost anywhere in the region, and it's given me my goal. I want to climb that mountain. It will come in time, but for now I think I'm going to spend some time meditating.

Some Beta

You do not need a guide to trek anywhere in the Khumbu region, but having one helps a lot - especially with the logistics of actually getting there.

Unless you have a specific camping trek planned, or are independently climbing a mountain that will require you to bivy, you do not need any camping gear except a water filtration system (mechanical filter + Steripen) and, optionally, a sleep system (sleeping bag + pillow) if you don't want to sleep in pseudo-clean sheets. There are lodges seriously everywhere.

Staying at a lodge will normally cost 500Rs ($4). Tea and coffee 100-200Rs ($1). Food 500-1000Rs ($4-9). Wifi, charging, hot showers 500Rs ($4) each. I probably averaged 3500Rs a day. Things get more expensive the higher you go, since everything was carried there literally on someone's back.

Altitude is real. Learn the signs and symptoms of AMS/HACE/HAPE, ascend slowly, take rest days.

Because of the above, expect to spend only 3-4 hours a day hiking and most of the day in a lodge. Bring something analog to entertain yourself (book, journal, cards), because charging is expensive and the Wi-Fi sucks.

During the main season, expect the main trails from Lukla to Everest Base Camp to be -packed-. The side valleys (Nongpa, Gokyo, and Imja) have less traffic.

NTC gets way better service than Ncell in Khumbu, but it's harder for tourists to get.

Stand uphill of pack animals lest they kick you off the trail. And if a herd is crossing a bridge, wait until they finish.

If you see any stones with weird writing on them, stupas, or prayer wheels, walk around them on the left and spin them clockwise with your right hand.

Tip your porters and guides generously (>20%). If it seems like a lot to you, think about how much it is to them. Porters especially are often subjects of abuse, if the obscene loads they carry on their necks could not already be considered as such.